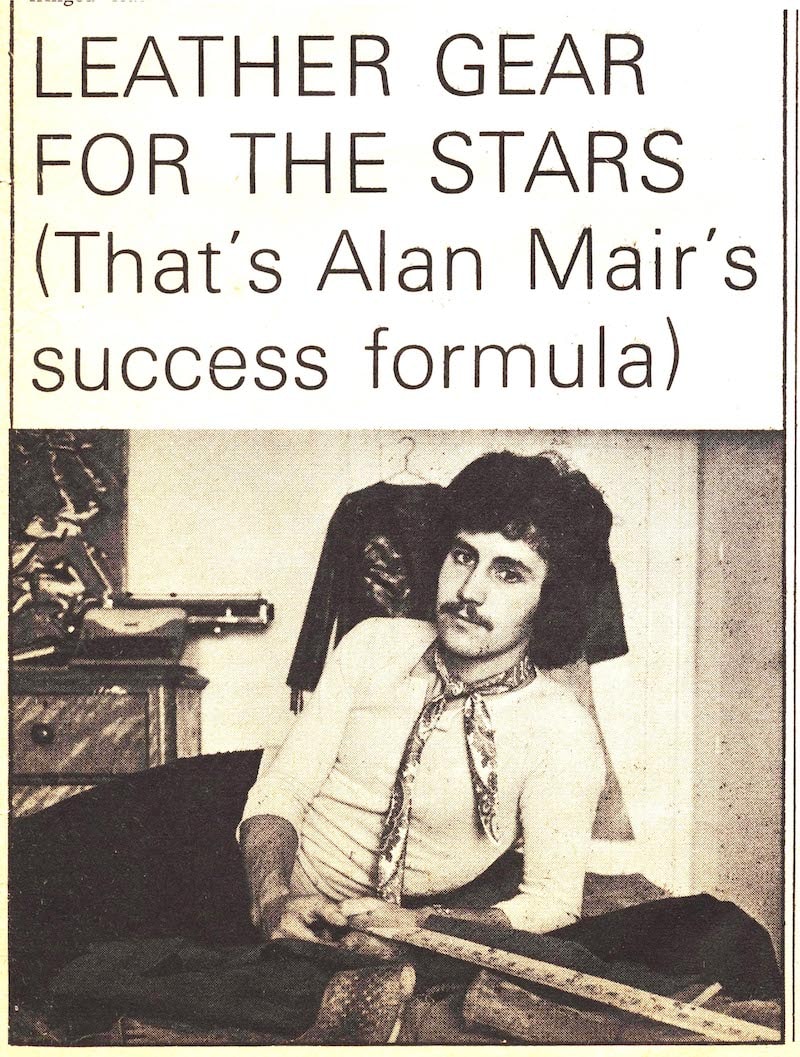

Alan Mair: Bootmaker to the Stars

Alan Mair, musician, songwriter, producer and perhaps best known as the bassist for the Only Ones and a member of Scotland’s 60s beat group the Beatstalkers. But for a short time during his 50-years plus in the music industry, he was also a clothes designer and boot maker.

Mair’s boots were made in his own factory, worn by the biggest names in rock. He exported around the world and sold them in his shops on Carnaby Street, King’s Road, Chelsea, and Kensington Market that was managed by up-and-coming frontman Freddie Mercury.

So, how did a musician with no background in fashion become boss of a global label? We caught up with Alan Mair to hear his story.

“When I was with the Beatstalkers, we’d travel down to Carnaby Street and it all seemed so stylish compared to Glasgow. It triggered an impulse. The band got big quickly and we’d have people making shirts and shoes for us. I began designing them. Making clothes came when we got a gig in Germany playing on the US bases.

“I’ve always been a curious person, wanting to know how to do things – I got it from my mum. The lady at the hotel reception in Germany used to sew in the back room. I wasn’t a party animal and I was married so I didn’t go out and party all the time. I often stayed in the hotel and watched how the lady sewed. As soon as we got back to Scotland I bought a sewing machine, it was about a year before the group broke up in 69.

“I knew a lot of bands so I started making clothes for them. When I moved on to working with leather, I loved it. I’d make trousers, fringed jackets and outfits for my wife. Then I did three-piece wedding outfits – skirt, jacket and coat – for musician’s wives. I had an appetite for it and with music industry connections ready customers.â€

Mair customised patterns he bought at John Lewis. He became known for flared trousers that had seams down the front and back – he’d bought a pair in Germany, taken them apart and adapted them. “I was married, so I needed stability and I had the inclination to make things. I was hellbent on making a name for myself.â€

In 1970, after navigating the politics of Kensington Market, Mair opened a shop there. “I had 15 pairs of trousers to sell and a cutting table and cow hides in the back. One day a French guy came in with calf-leather cut-offs, said he was in town for three to four weeks and could I get a pair of boots made for him.

“I drove around London looking for a shoemaker, they were mostly Greek back then and eventually I found Demetrius in Pratt Street, Camden Town, who had a shoe repair shop. For a pair of handmade boots, using the leather, size 8. I paid Demetrius wholesale £8. I sold them for £15.

“They hung in the shop until the guy came back for them and within that time I had orders for six more. It snowballed from there.â€

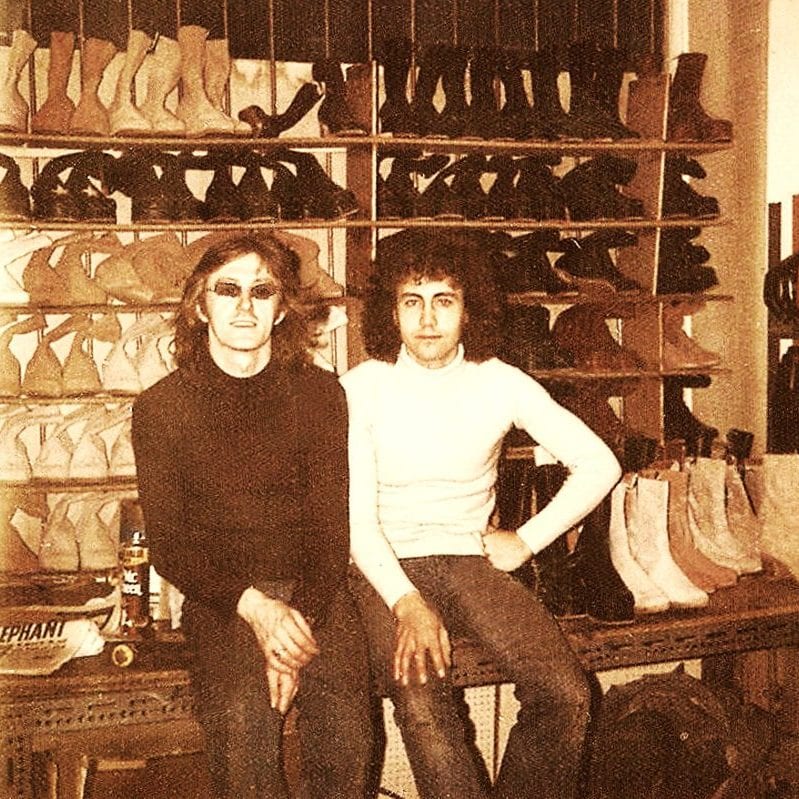

No one else was making anything like them and Mair was soon wholesaling to Italy, Germany and USA. Demetrius had six shoe makers working for him, but demand was outstripping supply and Mair turned his large workshop in Kentish Town into a small factory.

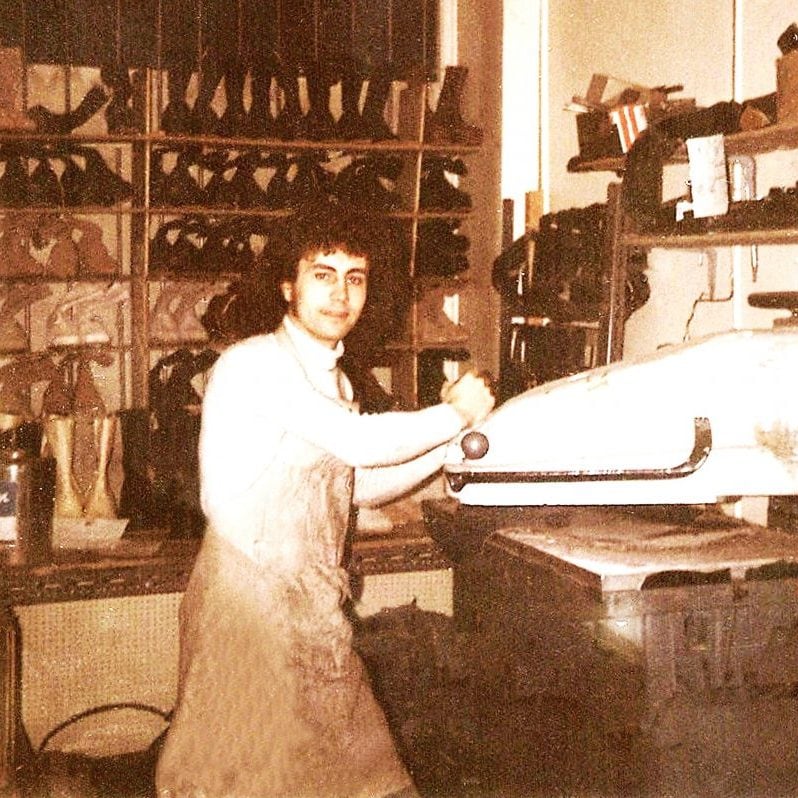

“Curiosity struck again,†he says. “Demetrius was producing the full supply, but I needed more so I watched him make them.â€

“The Demetrius boot uppers were still being cut by hand, so I started to buy cutting machines and equipment, and set up five stations in the factory: cutting, stitching, lasting, finishing and packing. I knew how to do every stage so that if anyone couldn’t turn up I could step in. I had friends working for me, including Eddie Campbell from the Beatstalkers. We didn’t stitch the soles, we used a heavy adhesive and when the heat lamps were on – I guess whoever was working there would have been high as a kite!

“Initially we were making 300 to 400 pairs a week. They had double leather soles with a stacked heel and anything between half an inch to 2-inch platforms. Then we did a three-layer sole and the middle one was a different colour. They all had a square toe, we never went in for pointed toes.

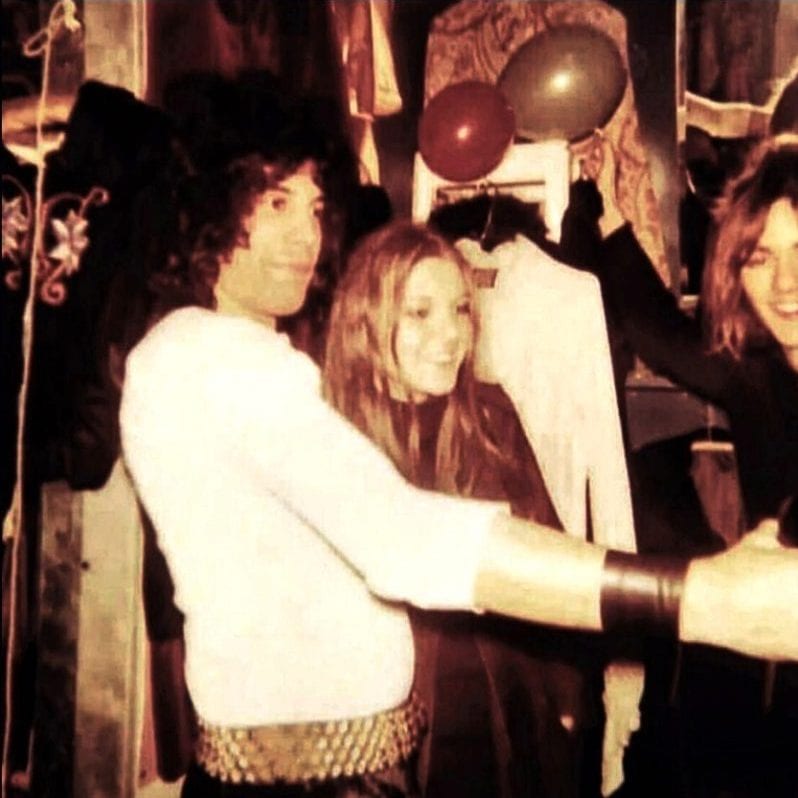

“In Kensington Market, after a couple of years, I’d become friendly with two guys opposite – Freddie and Roger. They were burgeoning musicians who worked at a clothes and jewellery shop. Freddie came to work for me in 70, he stayed until 74. We used to go to the Greyhound pub after we closed on Saturdays and one time Freddie said he’d been at a party and everyone, men and women, was wearing the boots. He said: ‘I don’t know if you realise, but you’re not considered cool unless you’re wearing Alan Mair boots.’

“We’d become well-known quickly, but because I didn’t go out galavanting, I had no idea how big we were. At the height, around 70% of the biggest groups around – the UK and USA – were wearing Alan Mair boots. I gave David Bowie a pair, because he couldn’t afford to buy them –he’d worked with the Beatstalkers for a short time. We must have been big, we had 10,000 bags made to use in the shop and they didn’t last long.â€

Below, left to right: Freddie, Roger Taylor and friend; Beatstalkers Eddie Campbell and Alan Mair; Mair cutting patterns

With the business flourishing, Mair began writing songs seriously again. He would find himself wandering down Denmark Street and eventually bought a bass. The pull of the music industry was getting stronger. Mair came to the decision that if he didn’t go back, he’d regret it. He’d made enough money to provide security for his family and so in 75 he sold half of the business to a guy who had a shop in Carnaby Street.

“I wanted to be a silent partner, but within six months I knew it wouldn’t work and closed it down. We had grown so much. The workshop was very personal to me, my friends worked there. They might not have stuck to a rigid timetable, but I didn’t worry as long as the orders were completed on time. We started off making hundreds a week, but now we had orders for 3,000 pairs a week.â€

Within a year, Mair was playing with the Only Ones and about to hit the big time. Again. He never kept any of his boots but recently bought back a pair from someone he found online, so now he has the hardware to go alongside the memories.

Mair’s last words are saved for Ops&Ops: “love the footwear you’re doingâ€. And we’re pretty chuffed about that!